Artwork created for the Repossessions exhibition is based on family ephemera from the enslavement and Jim Crow eras contributed by white families working toward repair.

Here are statements from each of the families who have contributed ephemera.

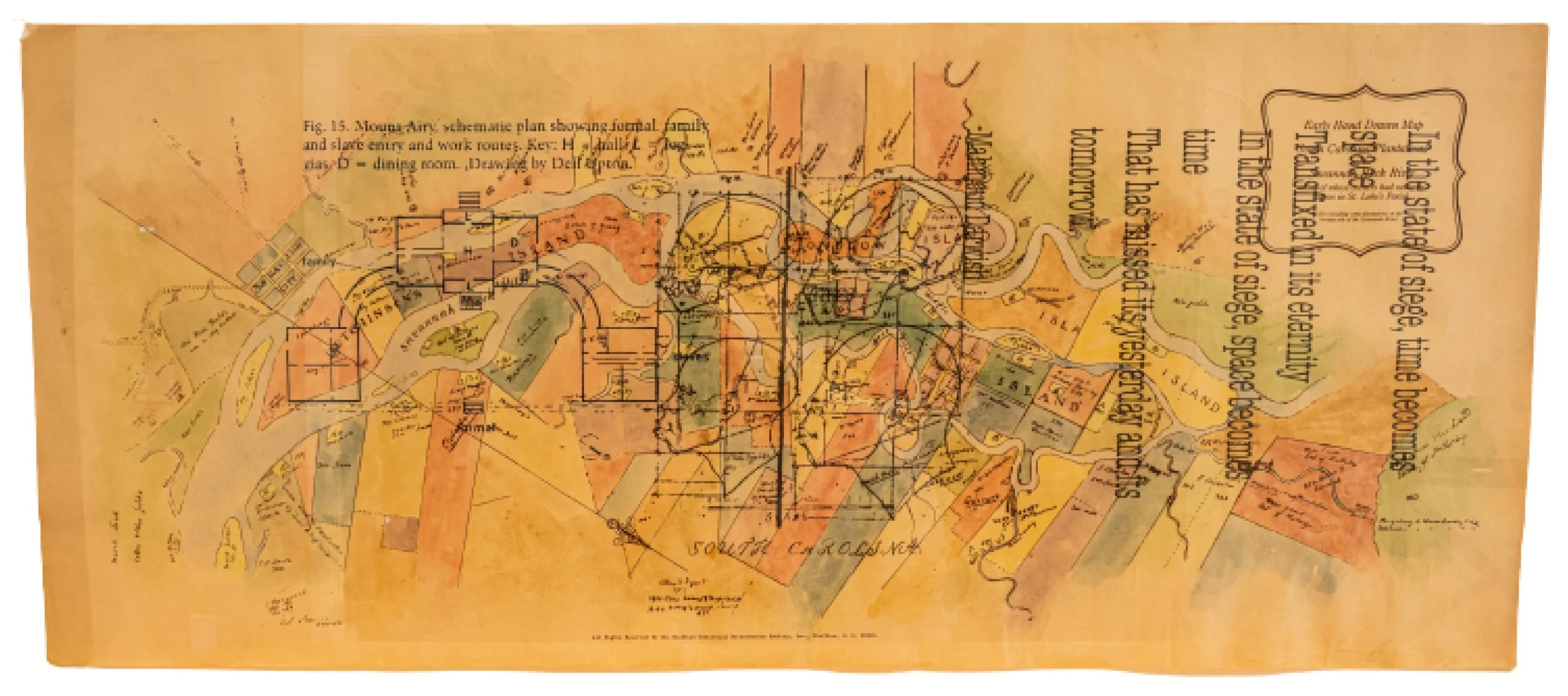

Plantation Map - Sarah Eisner

As we began to explore these three areas, I kept going back into that open closet. My mother and I rediscovered things we’d maybe passed over before or hadn’t seen; things that we began to consider what to do with and how to handle responsibly. She unfurled the water colored map of Savannah River rice plantations that usually leaned against the back wall rolled up in a tube and asked me again if I wanted it. It was something that had been bought sometime in the 1970s by my grandmother, not something the family had held for over a century. It was beautifully done, but to me, it was anything but beautiful. I could not look at the soft palette of pinks, yellows, and blues that identified Drakies and the other rice plantation plots without considering the brutality of enslavement, and its legacy. I could not appreciate the winding blue-gray brushed river without also knowing the ways in which Jim Crow laws continued to hold African Americans under the rising tide of white supremacy, and the ways in which it lingers today.

I did not want the map. But I did think I knew who to give it to….

Confederate Bills - Sarah Eisner

The confederate bills my mother rediscovered next were not in the closet in South Carolina. They, like so much of the same type of white supremacy that exists in the deep south, were hidden away unbeknownst to her, in a box in her closet in California. When I saw them, the idea for Repossessions came into sharper view.

“I should give these to a museum I suppose,” she told me. “They must be rare, maybe valuable.” Certainly, they felt momentous enough not to toss in the trash, and neither of us wanted to profit from them.

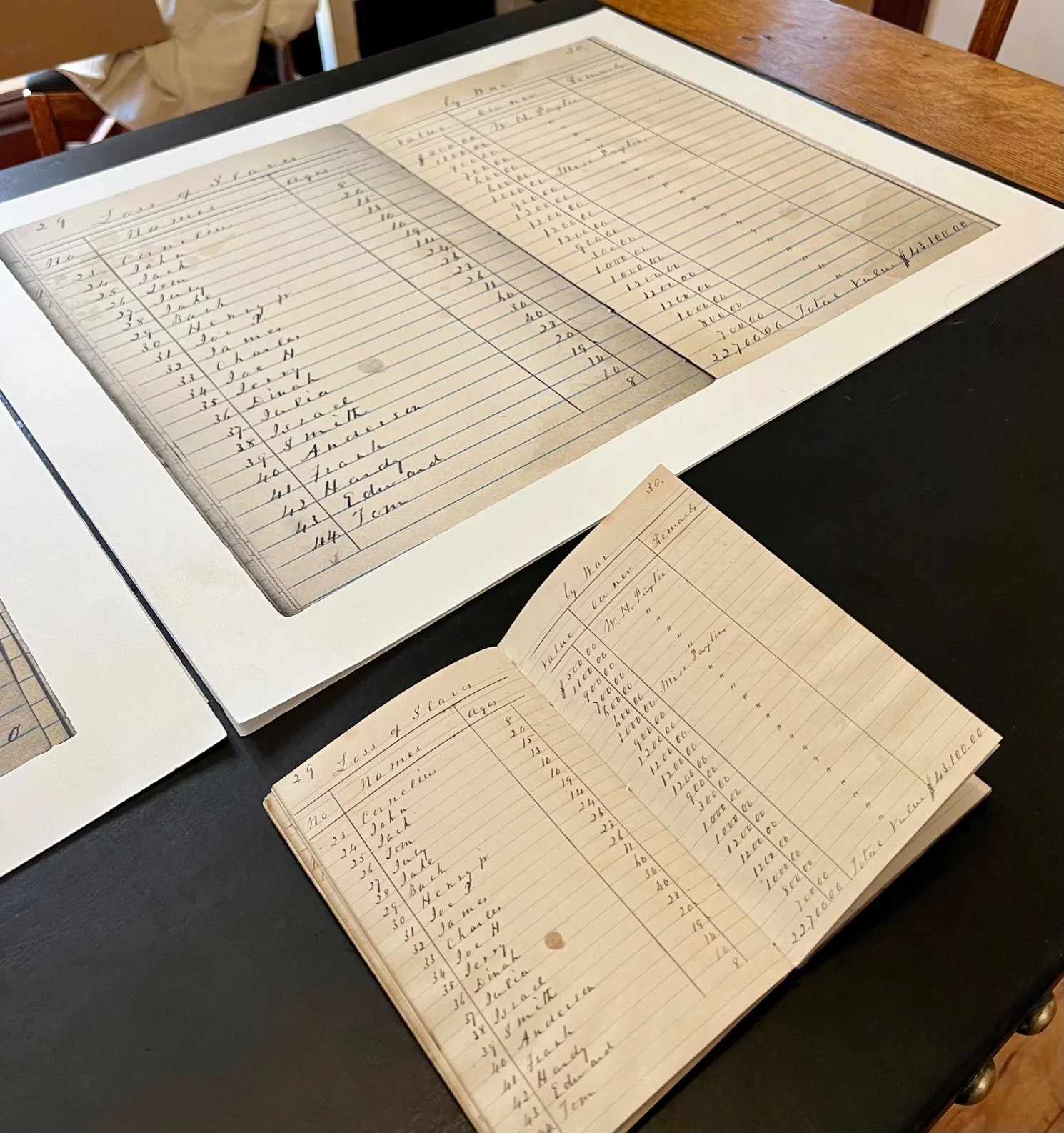

Plantation Ledger - Lotte Lieb Dula

The film "The Cost of Inheritance" begins with my discovery of this plantation ledger in a box of family ephemera. That finding is what propelled me to explore the reparations movement and try to engage in meaningful repair.

The heading on the ledger reads, “Loss of Slaves by War, 1861-1865.”

I believe that my ancestor, W.H. Paxton, may have used this ledger to petition the state of Mississippi for reparations due to his loss of “property,” including human chattel, by the conclusion of the Civil War. I believe I'm karmically linked to the movement for reparations to African Americans because of this ledger. It's a perfect mirroring; except, unlike my ancestor, I am petitioning for reparations for African American descendants.

Photograph - Jean

Image of African Americans picking cotton on the Lansford-Slaughter plantation near Huntsville, AL.